Saturday, 28 February 2026

EU approves Water lentils for consumption and production

The tiny green plants that float – and rapidly multiply – in stagnant water Water lentils, a protein-rich and sustainably cultivated plant have now been officially approved as a vegetable…

The tiny green plants that float – and rapidly multiply – in stagnant water

Water lentils, a protein-rich and sustainably cultivated plant have now been officially approved as a vegetable in Europe. It could make a significant contribution to the protein transition and the global food challenge. However, to achieve this, both producers and consumers need to become more familiar with this innovative vegetable.

Most people know water lentils as duckweed. The tiny green plants that float – and rapidly multiply – in stagnant water. In Thailand and other Asian countries, water lentils are eaten; they are primarily sold at local markets. Water lentils are not yet a food staple in the West, although the vegetable is hardly new. As early as 1644, a Dutch herbal book referred to ‘Water Linsen oft Enden Groen’ (Water Lentils or Duckweed).

Ingrid van der Meer first got interested in water lentils about ten years ago. The senior researcher and head of the Bioscience department at Wageningen Plant Research thought it was ‘a highly interesting plant’. ‘They have several biological processes that differ from those of other plants. From a scientific point of view, water lentils are very intriguing.’ For her research, the impression that water lentils left on her only grew. ‘They grow quickly, are suitable for contained cultivation and their dry weight contains massive amounts of protein.

In many ways, water lentils are an ideal vegetable for the future. ‘They are an exceptionally sustainable vegetable’, Van der Meer explains. “They are cultivated on water and don’t need many nutrients. Of course, water is a precious commodity, but in a simple greenhouse or vertical farm, growers can employ this very efficiently.’ The production of water lentils does not require any farmland, which means it can be grown indoors, even in cities. On top of that, growers do not need to use pesticides.

Technology

Ingredion Thailand Achieves 100% Sustainably Sourced Cassava

Feb 27, 2026 | Company News

Deakin University and Bellarine Foods Partner to Develop Sustainable Marine-Derived Proteins

Feb 26, 2026 | Australia

Royal Unveils Refreshed Jute Bag Design for 20lb Authentic Basmati

Feb 25, 2026 | Company News

Food Testing

Australian Medical Bodies Push for Compulsory Health Star Labelling

Feb 24, 2026 | Australia

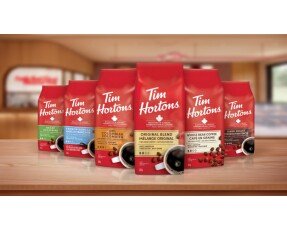

Tim Hortons Singapore Secures Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura Halal Certification Ahead of Ramadan

Feb 23, 2026 | Company News

More Popular

Fagron Acquires Pharmavit Europe for €68Mn to Expand Nutraceutical Portfolio

Feb 27, 2026 | Company News

Arla Foods Invests EUR 300Mn in New Cheese Dairy in Sweden

Feb 27, 2026 | Company News

Beyond Meat Broadens Portfolio Beyond Protein with Sparkling Plant-Based Drink Line

Feb 27, 2026 | Beverages