Thursday, 5 March 2026

Sugary drinks tax prevents decay and increases health equity: study

The study demonstrates a 20 per cent tax is cost-effective to prevent dental caries and is likely to increase health equity because the cost-savings and health benefits occur for populations…

The study demonstrates a 20 per cent tax is cost-effective to prevent dental caries and is likely to increase health equity because the cost-savings and health benefits occur for populations from lower socioeconomic advantage

A national Australian tax on sugary drinks could prevent more than 500,000 dental cavities and increase health equity over 10 years, a Monash University-led study has found.

Published in Health Economics, the collaboration with Deakin University and the University of Melbourne found that over 10 years, a 20 per cent sugar-sweetened beverage tax (SSB) had overall cost-savings of $63.5 million from a societal perspective.

The direct healthcare savings were $42.2 million, with 510,977 decayed teeth and 98.1 disability-adjusted life years – a measure of healthy life lost through premature death or disability due to illness or injury – averted.

Under a lifetime scenario for the current population until death, overall societal cost-savings were $176.6M, and direct healthcare savings $122.5 million, with 1,309,211 decayed teeth and 254.9 disability-adjusted life years averted.

“Our study demonstrates a 20 per cent tax is cost-effective to prevent dental caries and is likely to increase health equity because the cost-savings and health benefits occur for populations from lower socioeconomic advantage,” the authors found.

However, convincing governments and industry to implement it was a ‘major barrier’. The authors concluded that advocacy efforts should be directed at the Australian government “with a health equity lens, and with industry stakeholders”.

A single serving of a sugar-sweetened beverage (375 mL) has an average of 39 grams of free sugars (Food Standards Australia & New Zealand, 2019).

Study author Tan Nguyen, an oral health therapist and Monash University School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine PhD candidate, said SSB taxes had increased prices and decreased consumption internationally.

Nguyen said Australia had no such taxes and research from an oral health prevention perspective was limited. This was only the second study published on dental caries.

Technology

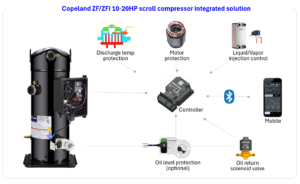

Copeland Launches ZF/ZFI 10-20HP Scroll Compressors

Mar 05, 2026 | Company News

WA Scientists Discover New Deep-Sea Crustacean Stocks with Strong Commercial Potential

Mar 05, 2026 | Australia

Food Testing

NSF and Circle H Collaborate to Enable Global Certification Access

Mar 04, 2026 | Company News

Australian Medical Bodies Push for Compulsory Health Star Labelling

Feb 24, 2026 | Australia

Tim Hortons Singapore Secures Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura Halal Certification Ahead of Ramadan

Feb 23, 2026 | Company News

More Popular

Copeland Launches ZF/ZFI 10-20HP Scroll Compressors

Mar 05, 2026 | Company News

Singapore Expands Support for Local Farms to Strengthen Food Security

Mar 05, 2026 | Food Security